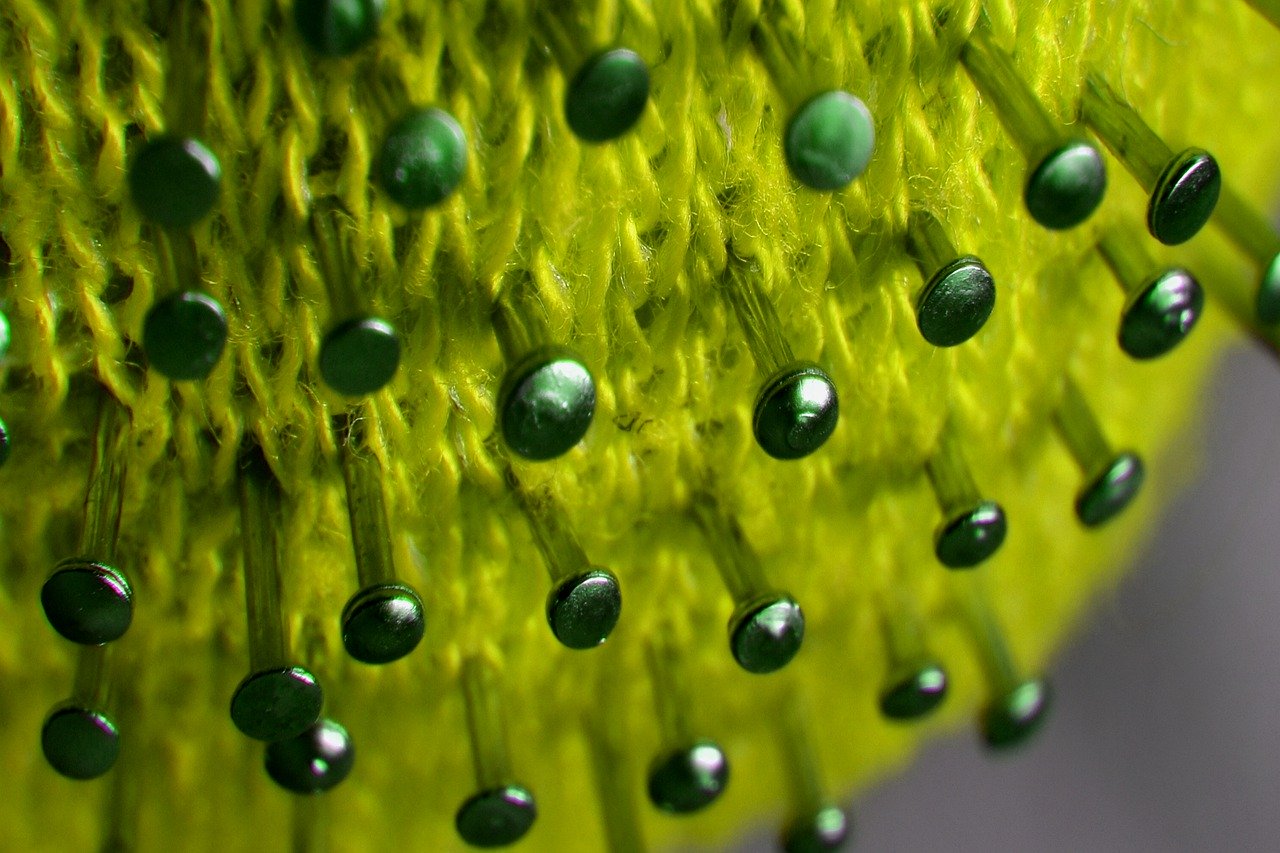

Photo credit: josefpittner, depositphotos

Last month, Commissioner Paul Rouleau rendered his much-awaited report on the use of the Emergencies Act by the federal government in 2022 to contain the Freedom Convoy and other such protests. While the principal feature of Commissioner Rouleau’s report has been his determination (made with reluctance) that ” the very high threshold for invocation [of the Act] was met”, I found his discussion of the right to protest to be of great interest.

He noted that the ability to protest is a “cherished right” and that it “empowers individuals to shape the rules by which we choose to govern ourselves, thereby enriching social and political life”. He cautioned that all rights, cherished though they may be, they are subject to reasonable limitations and that this had been lost to some who were caught up in the clarion call of “freedom”.

Commissioner Rouleau observed that the right to protest was protected under the Charter by three provisions: freedom of expression under section 2(b); freedom of peaceful assembly under section 2(c); and freedom of association under section 2(d). According to the Commissioner, when freedom of expression is exercised collectively through a public gathering to raise concerns about grievances, it takes on the characteristics of a protest:

Expression is inherent in the very idea of protest, since protests are, by definition, attempts to express grievance, disagreement, or resistance. The guarantee of freedom of expression in section 2(b) protects a person’s right to communicate a message, as long as the method and location of that expression is compatible with the values of truth, democracy, and self-realization. While violence and threats of violence are not protected, freedom of expression is otherwise broad. Expression can take an infinite variety of forms, including the written and spoken word, the arts, and physical gestures. There is protection for expression regardless of the meaning or message sought to be conveyed.

Freedom of peaceful assembly, as the collective performance of individual expressive activity, incorporates and advances many of the same values as freedom of expression. A public assembly or gathering can send a message of protest or dissent, forcing the

community to pay attention to grievances and become involved in redressing them. Public gatherings can enable disadvantaged and disempowered communities to forge a collective entity and leverage their voice.

He noted that the Charter only protects “peaceful” assembly – not all assemblies. And “peaceful” for him was not simply non-violent but would include some measure of disruption, although the line between what is an acceptable level of disruption and unacceptable “non-peaceful” disruption is often “blurry”:

Only “peaceful” assemblies are protected by section 2(c) of the Charter. As a matter of definition, “peaceful” might simply mean “without violence,” but it could also entail something closer to “quiet” or “calm.” A violent assembly would clearly not fall within section 2(c). The more difficult question is whether an assembly should lose constitutional protection if it is disruptive or unlawful, but not violent. In my view, it can be reasonable to protect assemblies that produce an element of disruption. Many public protests are disruptive, and that disruption may be central to their efficacy. This is especially true for groups and communities who are otherwise politically marginalized. This is not to say that all non-violent assemblies are constitutionally guaranteed regardless of how disruptive they may be. In some cases, the line between disruption and “non-peaceful” may be blurry.

Commissioner Rouleau underscored that all rights, including all the fundamental freedoms underpinning the right to protest, have limits and that, at some point, the government can take steps to curtail those rights and freedoms. He stated that the prohibition against public assemblies that was made under the Emergencies Act had to be carefully crafted because most of the protesters were exercising their constitutional rights to express their political views, something that is at the very heart of the fundamental freedoms:

This measure was also the one that most directly impacted the constitutional rights of protesters. Most of the participants in the protest were engaged in the exercise of the core right protected by freedom of expression: political expression. While some protesters may have crossed the line into violence, and at times and in places, the assembly may not have been “peaceful,” the fact remains that many protesters were engaged in conduct that is afforded significant protection under the Charter. For this measure to have been appropriate, it needed to be carefully tailored.

I think that Commissioner Rouleau has rendered a great service to Canada, its citizens and its democratic traditions. He has reminded us of the important values that underpin one of the often overlooked democratic rights, the right to protest — peacefully. Thank you Commissioner Rouleau.

I remain

Constitutionally yours

Arthur Grant

On April 19, 2018, in R. v. Comeau, 2018 SCC 15, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that New Brunswick was within its rights to control the flow of beer across its provincial borders: unrestrained interprovincial free trade in Canada (at least for beer) is still a pipedream. But imbedded in the Court’s judgment were seeds that, properly fertilized and irrigated, may well grow into a more robust protection of economic union.

On April 19, 2018, in R. v. Comeau, 2018 SCC 15, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that New Brunswick was within its rights to control the flow of beer across its provincial borders: unrestrained interprovincial free trade in Canada (at least for beer) is still a pipedream. But imbedded in the Court’s judgment were seeds that, properly fertilized and irrigated, may well grow into a more robust protection of economic union.